Why the Climate Change Summits Have Failed

K. Edward Renner, PhD

Greenhouse gas emissions are the principal cause of climate change.

For the past 1000 years the level of CO2 in the atmosphere has remained relatively constant at 280 ppm, but starting with the industrial revolution it has been increasing at an accelerating rate to 390 ppm, well above the upper safety limit of 350 ppm.

In December 2009 and 2010 the UN held Climate Change Summits to attempt to set world policy standards for limiting greenhouse gas emissions. The United States and China were the principle players as the two top green-house-gas-producing countries. Both Summits ended without a comprehensive agreement.

It is important to understand the reasons for these failures if the Summit this December in Durban in South Africa is to avoid a similar fate.

The United States has proposed that all countries should agree to absolute levels of reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. China has proposed that limits be set in terms of a proportion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). These are both self-serving proposals that neither can realistically expect the other to agree with.

Why do these proposals both represent bad faith negotiations?

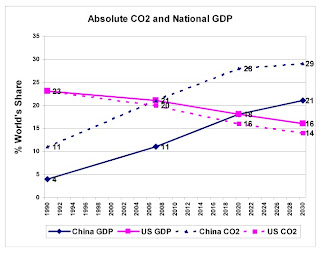

The US is rapidly losing its industrial base. From 1990 to the present the US lost 3 % of its share of the world Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and it is projected to lose even more by 2020. Because CO2 emissions closely track GDP, the projected decrease in the US share of world GDP will proportionally reduce its amount of CO2 emissions.

The position is self-serving because the US goal would largely be achieved without any change in current practices, and from new technologies already or in place or planned. On the other hand, this standard would severely impact China’s fast growing economy. As a world standard, it is an empty offer.

Source: International Energy Agency and Wall Street Journal

In contrast, from 1990 to the present China’s percentage share of the world’s GDP grew from 4% to its present level and is projected to increase to 18% by 2020. China’s position to set limits on the “intensity” of CO2 emissions as a percentage of GDP does not reduce emissions, but rather the rate at which emissions grow.

China’s proposal is also self-serving because without any change from “business as usual,” China’s projected intensity will naturally decline as a result of its increasingly larger share of the world’s GDP. (A constant excess of 10 units of CO2 is a smaller ratio of 18 units than it is of 11 units of GDP.) The remaining intensity reduction is already built into China’s development plan for fixing its own unhealthy quality of air. On the other hand, China’s proposal would seriously impact a US economy that has already achieved a lower level of intensity than China’s projected goal. As a world standard, it too, was an empty offer.

The position of both countries has not changed over the past year. To compound the difficulty, the world economic crisis makes it even more difficult for either country to agree to any policy that will make its economic recovery more difficult.

The challenge will be two-fold, first to find an alternative standard that is equally fair, and second to acknowledge that any immediate pain will be far less than what we will have to bear in the future if an agreement cannot be found.

In both the US and Europe we are already seeing that spending now and delaying payment until the future cannot continue indefinitely. The same holds true for greenhouse gas emissions. But the political capacity to act on that lesson is difficult, even though the necessity is obvious.

The challenge is to define an alternative world standard that is equally fair to both countries.

Professor Renner teaches in the Honors College at the University of South Florida. This material is based on his podcast series at: www.kerenner.com

No comments:

Post a Comment